Coordinated Batch Processing with Python and RabbitMQ

Apr 2020 • 6 min read

As an engineer, when you have a piece of processing work to be done, you’re always concerned with how best to achieve that work efficiently. i.e how can the work be done in as little time as possible, with the right amount of resources?

For most simple workloads, you likely don’t have to think about writing the most optimal process. You can get away with a simple for loop that iterates over all the items that need processing and you’re done. Simple and sweet.

When workloads start to get larger, things get more interesting. You start to realize that the for loop has begun to take longer to finish. You now need to explore ways to split that workload among different processes. With each process doing a bit of the work concurrently, your total processing time (TPT) reduces and you’re happy.

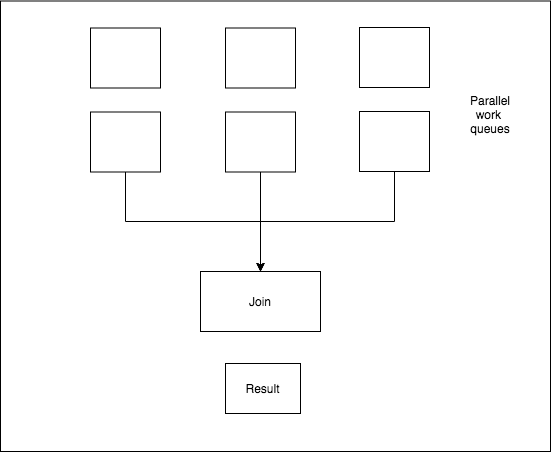

This concept is one of the various ways you can apply co-ordinated batch processing to handle complex workloads. In this post, we’ll be exploring a simple pattern for concurrent work processing, the join pattern, whilst writing logic in Python and providing work queues with RabbitMQ.

Requirements

Python 3

Python is one of my favourite programming languages, because of it’s principles. We’ll be writing the application logic in Python 3. You can install Python 3 using the official download page.

RabbitMQ

RMQ is a message broker system that we’ll be using to provide our sample work queues. If you don’t want to install Rabbit MQ on your system, you can go the Docker route like I did.

- Install Docker and Docker Compose.

- Create a

docker-compose.ymlfile in your root directory with this content:

version: '3'

services:

queue:

image: rabbitmq:3

ports:

- 5672:5672

- Run

docker-compose up -dto start RabbitMQ. You should now have RabbitMQ running on your machine on port5672.

Shakespeare: Counting Number of Occurrences

The sample work we are going to be doing, is counting how many times the word “more” occurs in a group of sample texts from Shakespeare. To make the amount of work we are doing more complex, I doubled all the text about four times into one large text file of about 45MB.

Since we are going to be re-using this logic amongst different queues, a good first step is to create a function that houses this logic, so it’s re-usable. This code lives in main.py so we can import it from each worker.

def count_words(words):

start = datetime.now()

count = 0

for word in words:

if word == "more":

count += 1

# Compute how much time the task took

diff = datetime.now() - start

print('Number of occurences:', count)

print("Total count time (ms):", diff.total_seconds() * 1000)

return {

"count": count,

"time (ms)": diff.total_seconds() * 1000

}

Aside: Rabbit MQ Concepts

Let’s look at the common patterns we use to interact with RabbitMQ, so we can understand them in the code. Connecting to RabbitMQ

Since we’re going to be connecting to RabbitMQ in the same way, it makes sense to highlight that logic here so we don’t need to declare it in all the code samples.

import pika

connection = pika.BlockingConnection(pika.ConnectionParameters('localhost'))

channel = connection.channel()

# Ensure the queue we need exists before using it.

# This block applies to all queues we publish to/consume

# throughout the examples.

channel.queue_declare(queue='process_words')

Sending Data to a Queue

To send data into a queue, we call the basic_publish method. We package the payload (which is JSON-encoded) and then specify the queue using the routing_key argument, with routing through the default RMQ exchange.

import json

payload = {}

# Send list to the queue through the default exchange.

# In this case the queue name is 'process_words'

channel.basic_publish(exchange='',

routing_key='process_words',

body=json.dumps(payload))

Consuming Data from a Queue

To listen for work on a queue, we call the basic_consume method. The arguments include the queue name and a callback function to perform the work.

import json

def callback(ch, method, properties, body):

print(" [x] Received")

# Listen for work items on the single queue.

channel.basic_consume(queue='process_words',

auto_ack=True,

on_message_callback=callback)

Now that we have an overview of how we’re working with RMQ, we can now discuss all the approaches we are taking.

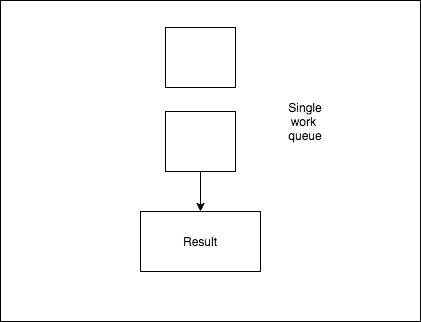

Approach 1: Single Queue

In this approach, we will send all the work items into a single queue and have one worker process all the items as once. It’s the bare minimum approach, so we can get time estimates and see if applying co-ordinated batch processing saves us time, or not 🤷🏽♀️.

To implement this, let’s split our logic into two files:

# single-mq-send.py

# ===========================================================

# Fetches the work items and sends to the worker

# queues for processing.

from main import get_words

from datetime import datetime

import json

# insert rmq connection logic

words = get_words()

start_time = datetime.now()

payload = {

'words': words,

'start_time': start_time.isoformat()

}

# Send list to the queue through the default exchange.

channel.basic_publish(exchange='',

routing_key='process_words',

body=json.dumps(payload))

connection.close()

print(" [x] Sent 'Hello World!'")

# single-mq-receive.py

# ===========================================================

# Creates a single worker to listen on one queue and

# processes the items as they are received.

from main import count_words

from datetime import datetime

import json

# insert rmq connection logic

def callback(ch, method, properties, body):

print(" [x] Received")

payload = json.loads(body)

count_words(payload['words'])

diff = datetime.now() - datetime.fromisoformat(payload['start_time'])

print('Total queue time (s):', diff.total_seconds())

# Listen for work items on the single queue.

channel.basic_consume(queue='process_words',

auto_ack=True,

on_message_callback=callback)

print(' [*] Waiting for messages. To exit press CTRL+C')

channel.start_consuming()

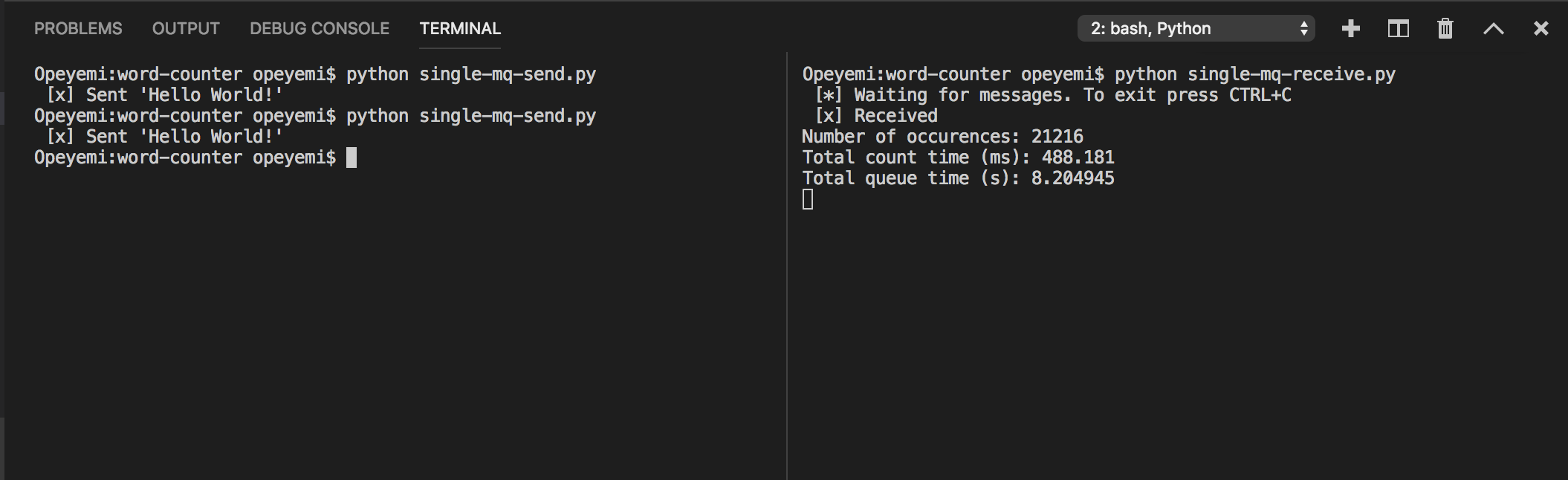

Results:

The total processing time (TPT) was ~8.2s using the single queue.

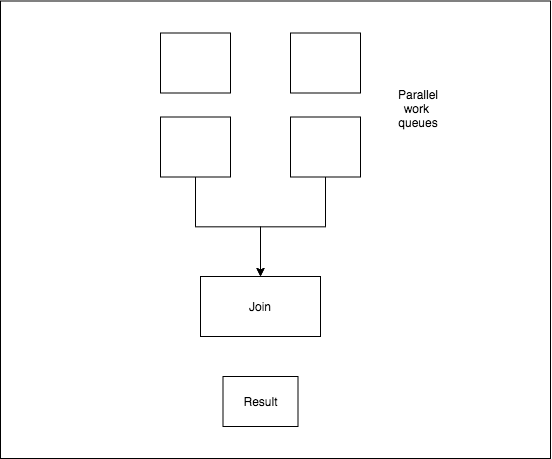

The Join Pattern (Two Queues)

The Join Pattern is a simple batch processing pattern, in which work is split into different queues and sent to a single queue to process the results. Hence the work is “joined” from multiple queues. In our example, we shall be sharding our work into multiple queues, processing them in those queues and computing the results in a “join” queue.

To make things even more interesting, let’s explore the differences between using two queues and three queues. My assumption is that with three queues we’d be able to reduce our TPT even further, but you never know. We also have to consider the communication overhead that comes with transferring our data between multiple queues.

Approach 2: Join Pattern with Two Work Queues

We first need our sharding function. Sharding basically means we are splitting the work based on some range. In this case we are splitting the work into two. i.e from range 0-mid, to range mid-end. The name of the function is split_array. You can check out the logic in the repo.

To implement the pattern we need three files:

# copier-mq-send.py

# ===========================================================

# Fetches the work items, Implements the sharding

# function and sends to the worker queues for processing.

from datetime import datetime

from main import get_words, split_array

import json

# insert rmq connection logic

words = get_words()

# Pass the start time so we can compute total time

# in the join queue.

start_time = datetime.now()

# Split words list into three

chunks = split_array(words, 2)

queues = ['process_words_1', 'process_words_2']

for index, queue_name in enumerate(queues):

payload = {

'words': chunks[index],

'start_time': start_time.isoformat()

}

channel.queue_declare(queue=queue_name)

channel.basic_publish(exchange='',

routing_key=queue_name,

body=json.dumps(payload))

connection.close()

print(" [x] Sent to both queues.")

# copier-mq-receive.py

# ===========================================================

# Creates workers to listen on both queues, process the items

# and sends them to join queue.

import pika

import functools

from main import count_words

# insert rmq connection logic.

# declare all queues used in this file.

def callback(ch, method, properties, body, queue_name):

# Body should be an array

print(" [x] Received")

payload = json.loads(body)

data = {

'queue_name': queue_name,

'result': count_words(payload['words']),

'start_time': payload['start_time']

}

channel.basic_publish(exchange='',

routing_key='process_results',

body=json.dumps(data))

queues = ['process_words_1', 'process_words_2']

for queue_name in queues:

cb = functools.partial(callback, queue_name=queue_name)

channel.basic_consume(queue=queue_name,

auto_ack=True,

on_message_callback=cb)

print(' [*] Waiting for messages. To exit press CTRL+C')

channel.start_consuming()

# copier-mq-join.py

# ===========================================================

# Receives results from all queues, waits for each

# queue to return a result and then computes the final result.

import json

from main import count_words

from datetime import datetime

# insert rmq connection logic.

# declare all queues used in this file.

# Track which queues have responded

state = {

'process_words_1': None,

'process_words_2': None

}

def callback(ch, method, properties, body):

# Body should be an array

data = json.loads(body)

queue_name = data['queue_name']

if queue_name not in state.keys():

return

state[queue_name] = data['result']

# Check if both queues have returned.

complete = True

total_count = 0

total_time = 0

for queue in state:

if not state[queue]:

complete = False

else:

total_count += state[queue]['count']

total_time += state[queue]['time (ms)']

print("Time added", state[queue]['time (ms)'])

# Compute result

if complete:

diff = datetime.now() - datetime.fromisoformat(data['start_time'])

print ("Total number of occurences:", total_count)

print ("Total compute time:", total_time)

print ("Total processing time (s):", diff.total_seconds())

# Listen for work items sent to 'process_results' queue.

channel.basic_consume(queue='process_results',

auto_ack=True,

on_message_callback=callback)

print(' [*] Waiting for messages. To exit press CTRL+C')

channel.start_consuming()

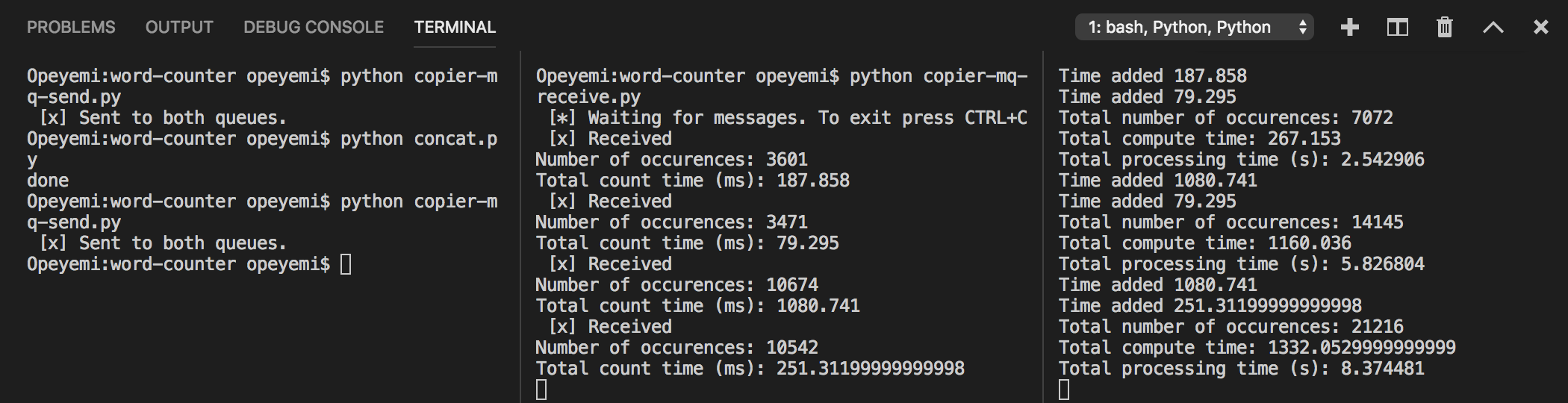

Results:

The TPT was ~8.4s using two queues.

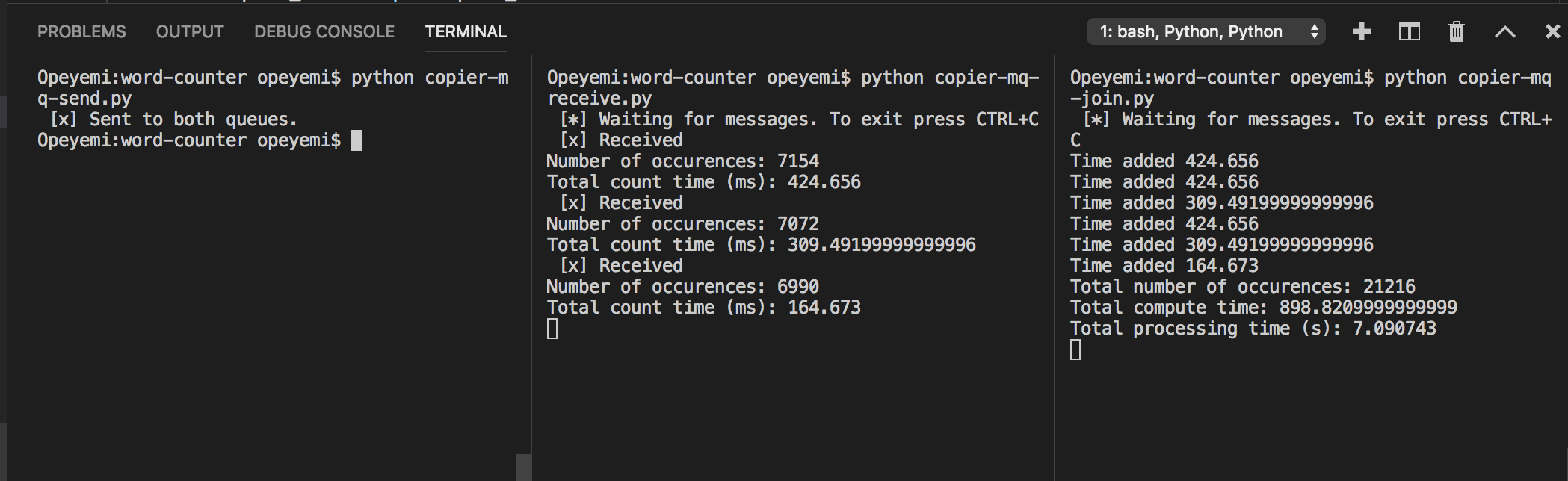

Approach 3: Join Pattern with Three Work Queues

Since the main difference in the code is adding process_words_3 to all the code blocks concerning queues, and increasing the size of the sharded array to 3, I won’t be repeating all the logic. What we’ve done though, is split the work amongst three queues, so we expect a shorter processing time.

Results:

The TPT was ~7s using three queues.

Side Note on Concurrency vs. Parallelism

When I first wrote this post I believed this was parallel processing, but it’s not. Instead it is concurrent programming.

Based on their definitions, Concurrency means multiple tasks which start, run, and complete in overlapping time periods, whilst Parallelism means when multiple tasks run at the same time e.g. on a multi-core processor.

The faster processing in this pattern comes from this concurrent processing using multiple queues.

Another interesting thing to note is that it is almost impossible to do parallel processing in Python using multi-threading because of a process known as the Global Interpreter Lock.

Conclusion

The results of all the tests are:

- With a single queue, the TPT was ~8.4s

- With two queues, the TPT was ~8.2s

- With three queues, the TPT was ~7s

I also noticed that as the size of the workload increased, the gap in TPTs between using a single vs. two vs. three queues increased. This reinforces that coordinated batch processing (CBP) gets more important as your workloads increase, and it’s always a good idea to keep thinking about how you can leverage CBP patterns to make your processing cheaper, saving yourself and your company costs in the long run.

To help me grow on Youtube and learn about Monitoring, Machine Learning, and SRE, please subscribe here.

And to get notifiied about new posts, please subscribe here.