Auto-remediation is important

January 2025 • 5 min read

Building software at scale is hard. Maintenance is even harder.

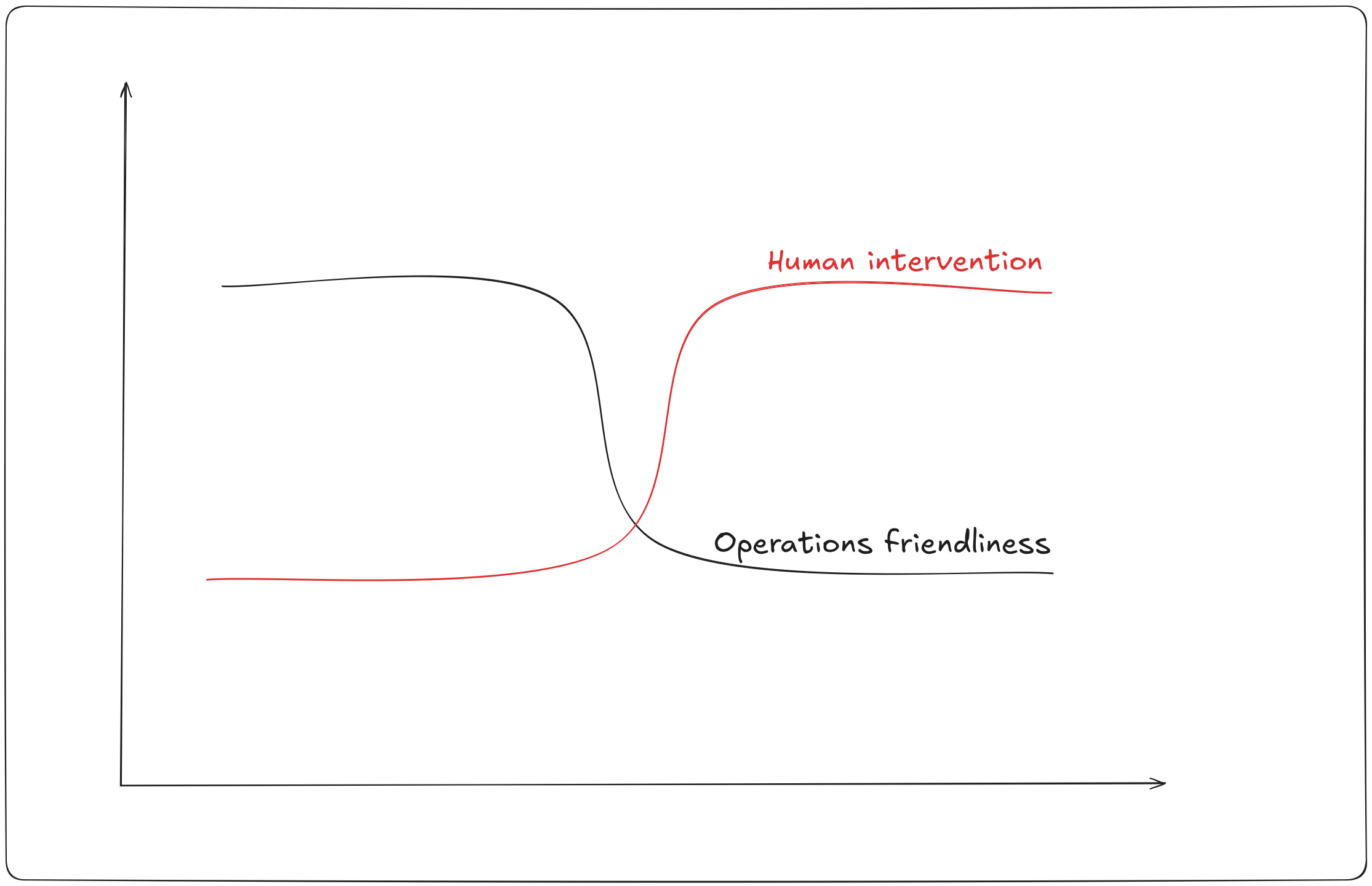

No company can succeed without a solid approach to handling operational problems. Failures will happen. As fleet sizes cross 10,000 servers, services need to be increasingly operations-friendly 1. Each service should run with as little human intervention as possible. Unfortunately, Operations teams such as DevOps and SRE still find themselves intervening regularly.

There are several considerations when building an ops-friendly product. Some examples are designing for scale, providing redundancy, and building automatic failure recovery. As an experienced SRE, I have a vested interest in the last item, failure recovery without human intervention. How do we get there?

In 2018, a payment outage left millions of Visa customers in Europe unable to make payments with their cards. This caused widespread panic, and rightly so. Customers want assurance that their money is safe and accessible. The postmortem revealed that a faulty datacenter switch caused a number of transaction failures. Considering it took ~10 hours for the issue to be resolved, I think it’s safe to say that a lot of people worked together for a while to get the fix out. Without intervention, it would’ve been even longer.

Before fixing problems through intervention, engineering teams need to first know when they happen. This is why Monitoring and Alerting are fundamental to preventing high-impact incidents. An alert queries a metrics system for a known problematic condition and notifies a responsible stakeholder when there’s a match. The alert priority then determines the level of intervention required.

This approach scales across teams, organizations, and companies. Although the nature of the alert may differ due to differences in what is monitored, the approach itself is reusable. An engineer who is responsible for a product’s customer experience may receive an alert when there is a spike in user errors, while an infrastructure engineer who is responsible for a database receives an alert when the database’s CPU utilization is beyond a threshold.

At a small company, it will often suffice for a human to respond to every alert, as it is not expected to be high volume. As the company grows in size, however, the number of alerts may increase exponentially. Responding to every alert is no longer easy to do, and the toilsome nature of some alerts is exposed. This is when engineers typically explore ways to automate alerts. Toil reduction is a reasonably strong motivating factor. Toil is any response/action that is repetitive and brings no enduring value.

A common initial approach amongst ops engineers is shell scripting. Responders can run the shell scripts to reduce the time taken to resolve the alert and eliminate room for human error. Meanwhile, a product engineer may rewrite the behavior of the software to fix any latent bugs or improve performance. They may differ in their eventual solution, but both examples involve writing some code to resolve alert conditions.

While shell scripts and code fixes make response easier, they still require human effort. This effort does not scale with company offerings. Soon enough the response becomes hectic again. Some alert response procedures require communication with external systems and teams. When I worked in fintech, a provider could go down randomly. The product team’s responsibility was to ensure that the failure was handled gracefully e.g. by switching to a backup provider. But that wasn’t the end.

They’d then need to reach out to the provider, to get the issue resolved. Sometimes the first phase is automated, but the second is manual. I have found recently that human communication in failure response is a great candidate for automation. A system can start an email thread with a partner, or page the on-call of a dependent service team.

As alert volumes increase, invest in software to handle routine failures. It is worth noting that early-stage companies typically run in cloud environments and bear less of a burden of infrastructure recovery, especially from hardware failures. The cloud provider automatically handles infrastructure failures. Some cloud features also provide self-healing capabilities. AWS autoscaling will increase capacity in high-load conditions, preventing resource utilization problems. GCP has autohealing that can automatically restart an instance based on health checks. In some cases, however, this may not be enough. A service may face unique failure conditions based on the architecture and nature of the product offering.

It is also common to use an orchestration system such as Kubernetes. Hardware failure recovery is baked in here —- if a node becomes unhealthy the tasks are rescheduled onto another. Services can then further implement “self-healing” by designing for reliability. A simple example is a service health check which can cause a task to be rescheduled on failure. It’s good that platforms nudge users to these best practices by default, so they can implement basic self-healing without reading a 1000-word blog post.

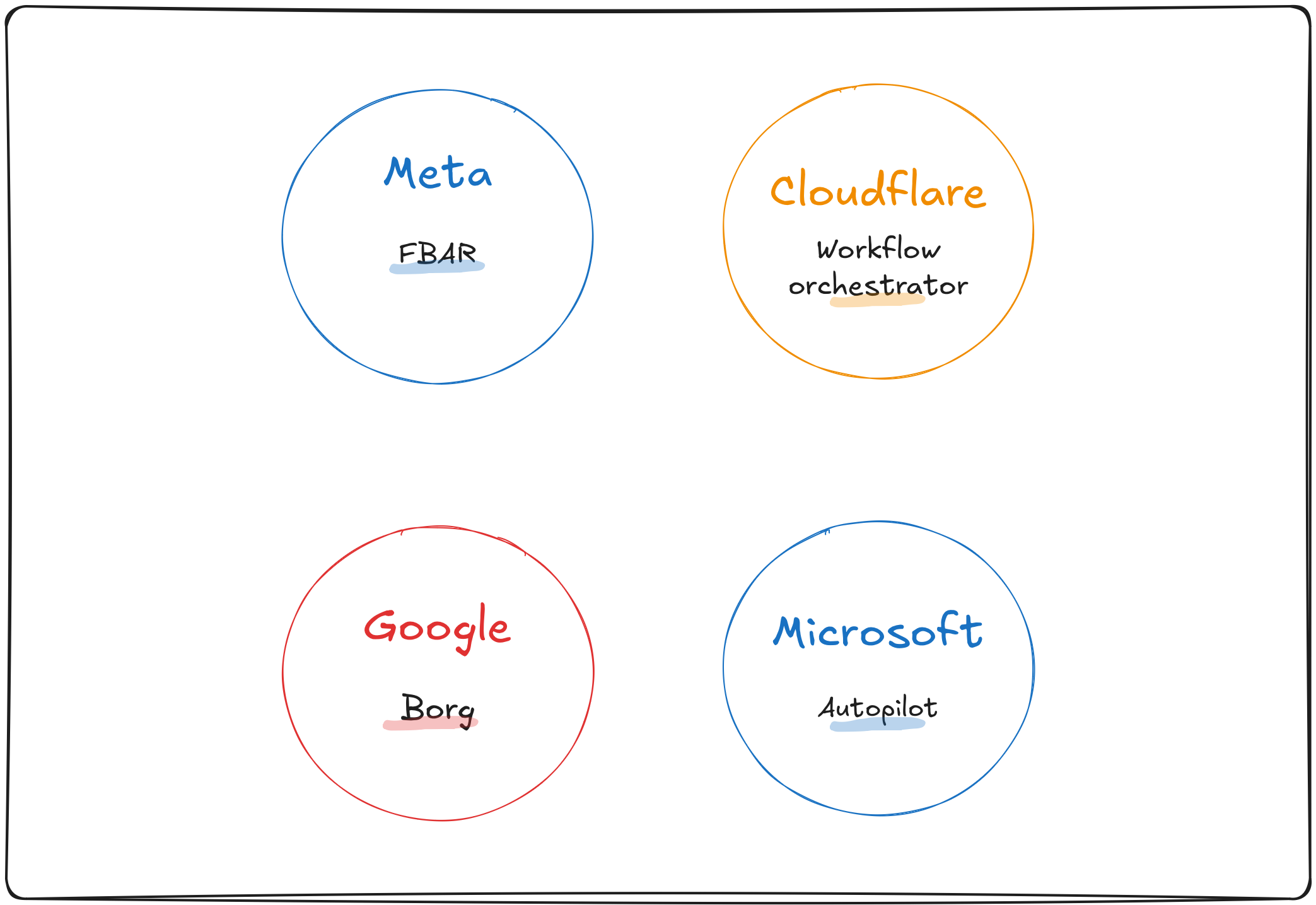

It is common to find on-premise infrastructure in larger companies. When you own both the software and hardware, it’s more likely that you need to think about infrastructure auto-remediation. This is why these companies have had to solve problems from the bottom up and have created well-known solutions. These solutions often form the basis of cloud offerings and other well-known orchestration systems.

Kubernetes for example was based largely on Borg, a large-scale cluster management system developed by Google 2. Meta has described FBAR, an auto-remediation system that was initially designed to automatically recover from hardware failures but has since been extended to service owners for custom remediation 3. Microsoft Autopilot automates provisioning and deployment, as well as recovery from faulty software and hardware 4. More recently, Cloudflare described an auto-remediation system built by SRE to kill toil, with additional reliability provided by durable execution technology (the author should look familiar) 5.

Having built one from the ground up, I have seen firsthand how transformative an auto-remediation system can be. Reducing toil and making on-calls less stressful is one thing, but creating a shared strategy and vision is even more beneficial. I intend to write more long-form material about how to design such a system and achieve ops-friendly environments. For now, you can read the article on the Cloudflare blog. If you have any questions or something you’ve found interesting, please reach out. I’m particularly interested in companies where this is less of a problem that needs solving - things just seem to work. Why?

The future of remediation is something I think about often as well. With the recent AI boom, it is difficult not to get drawn into the potential. Meta has described how they’ve used a machine learning model to predict what remediation might be required when a hardware failure occurs 6. I haven’t seen anything public from Google, but I haven’t done much looking yet. I will write about my findings in another blog post.

But for now, my thoughts.

Tooling that enhances diagnosis for faster recovery would be a game changer. It’s easier to start with platforms like Kubernetes since they have established concepts/patterns to train a model. Ultimately, any tool that can understand the environment can enrich alerts with recommendations, spot regressions, automatically silence problem patterns with no impact, etc. Depending on the confidence rating of recommendations, it would then be worth considering whether to feed those back to the auto-remediation system to take action.

The concept of an operations-friendly system is not restricted to operations teams. To me, operations here means “running in production”. As a product engineer, your daily intervention count matters. It should be pretty easy to tell if your product isn’t ops-friendly. The good news is that this is an opportunity for you to bring value to your team and show leadership. With time and patience, you can untangle any complex webs and break them down into fundamental engineering problems. Chances are you don’t need to build auto-remediation first - you just need better design. I recommend reading the paper “On Designing and Deploying Internet-Scale Services” for more information 1.

A shareable pdf of this post is available here.

Speak soon.

Footnotes

-

James Hamilton - On Designing and Deploying Internet-Scale Services ↩ ↩2

-

Google - Large-scale cluster management at Google with Borg ↩

-

Meta - FBAR (Facebook Auto-Remediation) was initially described in Making Facebook self-healing ↩

-

Microsoft - Automatic Data Center Management ↩

-

Cloudflare - Improving platform resilience at Cloudflare through automation ↩

-

Meta - Predicting Remediations for Hardware Failures in Large-Scale Datacenters ↩

To help me grow on Youtube and learn about Monitoring, Machine Learning, and SRE, please subscribe here.

And to get notifiied about new posts, please subscribe here.